Science is funny. Over the last few days my project was in a conceptual crisis, then I found that crisis was just what I needed to make it something great. Hopefully I learned a thing or two along the way.

My initial project idea revolved around measuring thaw depth at different points around the major Y4 channel to better understand and potentially predict changes in erosion that could occur with the deepening active layer we see across the arctic. I hypothesized that there would be a link between the active layer depths and the amount of erosion we could see.

I was excited, imagining meanders forming faster, more river sediment, and deeper river channels as the arctic warmed. But as I thought harder about the methods, and about what we could quantitatively measure, I realized this project was not feasible. I feverishly paced the buggy path from the barge to the station, trying to think of a way to acquire erosion data, mumbling thoughts to myself.

“I could stick a ruler in the side of the bank… No… This water is practically stagnant. It won’t be detectable”

“What if I just throw chunks of active layer and permafrost soil in the channel? Sure… That would give really consistent results… not.”

I locked myself in my bunk room. Ear plugs in, eyes closed, my mind began to race.

“Putting a slug of salt upriver and measuring the salinity spike downriver is a technique to measure flow… What if I put a block of salt in the bank?”

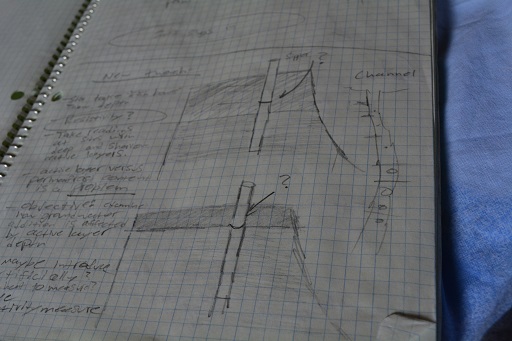

My eyes opened wider than they should in the bright arctic afternoon. I began scribbling in my notebook. This salt measurement wouldn’t measure erosion, not exactly, no. It might indicate groundwater flow. Why had I been interested in erosion in the first place? The arctic is a surface water dominated system at the moment, the water simply can’t seep through the permafrost to make deep groundwater systems. I had thought that measuring erosion at different active layer depths might give us some insight but this….

I rolled back on my cot, a smile creeping across my face, and continued jotting down my thoughts. This is even more relevant to understanding potential changes. I can use sippers, pipes inserted into the ground to collect water samples, for readings on the sub-surface water in the soil. The salt or flow indicator isn’t the important part, the contents from the water samples we collect is the critical part. What if I soak soil samples by the bank and measure what’s in that water? Is that reasonable?

I ran off to find John.

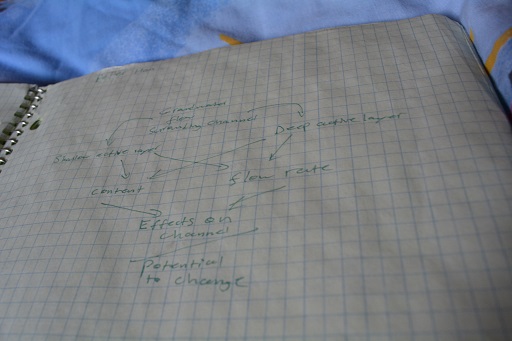

After long talks with John, Ludda, and Paul, my project took a more defined shape. There are still problems, I need to consider thawed permafrost versus active layer soil, and little is known about the subsurface water around this particular channel, but these are problems that I can work with, and they can even enhance the study. As Paul said of my new idea, “it’s got legs.”

There’s my process, running into a barrier made me reassess my project, and doing so brought me closer to my big question. That’s science, thinking about the question, refining it, and going about answering the question to the best of our abilities.

On our way to Duvannyi Yar, leaning against the barge, watching the midnight sun’s reflection in the river, all I could think was “I’m in the arctic, studying where the soil meets the water, on my way to a cliff filled with ice age bones. I couldn’t be happier.”

And Science is awesome.

Comment(1)-

Joanne says

July 18, 2013 at 7:03 amHyporheic flow is so awesome! There may be some shallow piezometers somewhere there; I remember leaving behind a few. Good luck with your project!