We are stardust,

Million-year-old carbon.

We are golden, but caught in the devil’s bargain,

And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the Garden.

“Woodstock” Joni Mitchell

One of our PIs Jorien Vonk finished her Ph.D. last year at the University of Stockholm. She studied the “remobilization of old carbon” during its transport from rivers to the Arctic Ocean. A friend, a nonscientist, congratulated her on her success and then asked, “What are you going to do now?”

Decked out in her bug shirt, lifejacket, waterproof pants and rubber boots, Jorien sits with her gear in the inflatable boat she and Eirik will take out on Airport Lake to collect data and samples. © Becky Tachihara

Certainly not a dumb question, but it points out a misunderstanding among the rest of us about how this kind of science works. After four years of concentrated effort and travel to remote places, hadn’t Jorien learned all there was to know about river-to-ocean carbon transport in the Arctic? Well, no, she will likely devote her entire career to the problem. She might “move farther up the rivers,” as she put it, but she won’t go far from the Arctic or old carbon. The question she’s grappling with is just that complex.

But I can empathize with her friend’s misunderstanding. Until a few years ago after a sequence of coincidences introduced me to their world, I had never even met a professional scientist. I’d met a couple of science writers, but no real scientists. We just don’t travel in the same circles. When in the 19th century people spoke of culture, they spoke of art, literature, drama, music, and science. No longer. Now science is segregated. Now we think of it, if we think of it at all, as an esoteric, even arcane endeavor, riddled with impenetrable jargon and spattered with acronyms, a bit geeky, and too tough for little ole me. Besides, I’m pretty busy these days.

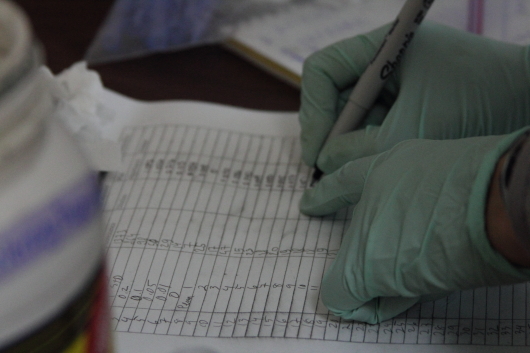

Laurel fills in a chart with the results of chemical tests she and John have been running on water samples gathered from various streams throughout the Kolyma River watershed. © Becky Tachihara

But when you get right down to it, scientists, no matter their particular professional concentration, seek to understand how the natural world works. We live in the world. Isn’t that sound reason for the rest of us to look over their shoulder as they work? The trouble is, nature is dizzyingly complex, the word nature misleadingly singular. Nature’s systems are multiple, full of cycles, oscillations, variations across all timescales, and layered fluxes that don’t readily reveal themselves to the honest seeker. Far too much data has been collected, research performed, technology developed, knowledge accumulated since, say, Darwin’s time when science was called “natural philosophy” and when the great man learned all there was to know about botany, geology, and biology, for any contemporary scientist to call him/herself a generalist. Even a specialist can’t know their entire specialty. That means that there are too many shoulders to look over all at once. The word scientist is likewise misleadingly singular.

Jorien’s an intrepid, tough field scientist. Watching her disappear into mosquito-ridden hellholes (MRH) to sample water in a flood-plain lake, I was glad my work didn’t require me to go along. She was after the carbon, never mind the conditions. She’s not alone in that. Everyone in this project is equally committed and intrepid. She—like me, like the ambitious rest of us—is doing her work for personal reasons, to satisfy curiosity, say, or to attain a level of peer prestige, any number of personal motives no more altruistic than nonscientists’. And so what if we choose not to pay attention to what scientists are doing? It’s not like they’re paying unbalanced attention to what we’re doing. Besides, they’re pretty busy following the carbon.

However, something quite new has reared its head in the relationship (non-relationship?) between scientists and the rest of us. Now science itself has come under attack by a well-funded, well-organized, and politically well-connected opposition. That opposition has exploited our ignorance of what scientists do and how science works to perpetrate their corrupt agenda. To wit: There is no such thing as global warming. But if there were, it would be just another natural cycle; it’s not our fault. And even if it were our fault, there’s nothing we can do about it without ruining our beloved economy. Even more irrationally and much more nefariously, this opposition accuses scientists of perpetrating a vast climate-change conspiracy to frighten us about climate-change doomsday in order to pad their grant money. Can’t you just picture it, 22,000 scientists gather each year for the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in San Francisco, biologists, botanists, oceanographers, biogeochemists, physicists, you name it, and all manner of subdivisions within each, people who don’t even speak each others’ technical lingo, and they’re all plotting, probably on Castro Street, to sell us their global warming scam.

“What’ll we give ‘em this year?” Heh-heh, mustache twirling.

“How ‘bout we run the old sea-level rise routine? We’ll show the sods that map of Florida, everything south of Disney World underwater.”

“Good, that gets ‘em right where they live.”

“Just don’t get too technical.”

“Yeah, remember, they’re not too bright.”

Preposterous. Idiotic.

Yesterday morning our PI Andy Bunn gave us the presentation he gives to interested groups of nonscientists. He speaks down to no one, nor does he advocate for a particular course of action in response to global warming. It’s only the physics. And the physics is simple: Carbon dioxide is a heat-trapping gas. We’ve known that since 1859. This is not a new idea cooked up at the AGU. We know, further, that since the Industrial Revolution, the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen steadily, even accounting for seasonal variation. One of the things scientists do is measure. We now have the instruments to measure atmospheric carbon dioxide. It’s gone up from 280 parts per million to about 390 ppm—and continuing to rise.

Then Andy made a neat point. There’s not all that much money to be gotten by proving something everybody already knows. If on the other hand, he could prove that carbon dioxide is not a heat-trapping gas, or that its quantity in the atmosphere is not increasing—that would make him a famous and fortunate paradigm shifter. “It would be Darwin, Einstein, and Bunn,” he said.

The sun hangs low over the horizon, creating a shining path on the surface of the Panteleikha. © Becky Tachihara

Since the physics is so straightforward, the naysayers have had to hustle to find a route of attack. One reason they’ve succeeded to the extent they have is because of our assumption that science is hard. They throw in some pseudo-scientific jargon, natural cycles, blah-blah, Al Gore, blah-blah, enemies of free-market capitalism, global cooling in the ‘70s, elitist pinkos, blah-blah-blah. They are the ones who think we’re stupid. What we decide to do or not do about global warming is one thing—we have some choice about that. But we can’t argue about the science, about the physics. It’s laughable, therefore, to say, “I don’t believe in global warming.” Physics is not an issue, like, say, the place of prayer in public schools about which we can argue. Physics is not faith-based.

I used to wonder why, in the face of this vicious excoriation by charlatans and know-nothings, scientists didn’t stand up and fight back. Having learned a bit more about what scientists do, I no longer ask that question. Scientists deal in facts, the very things the naysayers intentionally corrupt, and so ends sensible discourse before it begins. Further, as an intellectual precept, scientists are skeptical; you’ve got to prove it. Scientific skepticism is not inherently compatible with soapbox advocacy. Also, as Paul Mann, another of our PIs, put it, “What do you want us to say that we haven’t already said?” He was referring to the IPCC Assessment Reports. Hundreds of scientists from dozens of disciplines and dozens of nations got together, and after considering thousands of peer-reviewed papers, hashed out the language—and came to a consensus. Imagine, all those disciplines, all those nationalities coming to a consensus: Human-induced warming of the climate-system is widespread.

The group walks along a ridge, making our way across the tundra toward the Sukharnaya River. Of all the places our scientific ventures have taken us, the trip north to the tundra boasts some of the most beautiful and tranquil scenery. © Becky Tachihara

Scientific discoveries are communicated via peer-reviewed technical journals. We would find most of them impenetrable; so would, say, a forest ecologist trying to read a piece in The Journal of Physical Oceanography. They, like today’s science, are and must be highly specialized. Careers are measured not by the research you conduct, but by the papers you publish about it, and it’s tough to get a paper published, because of the peer-review process. You have to prove your point with data, and your results have to be duplicable to the satisfaction of a panel of your peers. The process can take over a year from submission, through revision to final publication. Acceptance rates compared to submissions are small.

Several years ago a very smart historian of science named Naomi Oreskes counted all the peer-reviewed journals dealing directly or indirectly with climate change. There were tens of thousands; the actual number has since been updated. And she compared them to the number of papers that proved that climate change was nonexistent. There were none. Zero.