It’s a beautiful morning in Siberia after a couple of days of rain, the sky cobalt blue, bright sun glinting on the distant flood plain lakes and sharpening the contrasting shades of green between stands of larch and low-lying bogs. Layers of flat-bottomed cumulus clouds, the sort seen in the tropics, are forming over the eastern horizon. But today is different. Today, scientists and student scientists are scurrying to enter on spreadsheets, to graph, and to double-check the last of their collected data. Some are cleaning the wet lab, the soil and the summer labs, while others are packing up clear-water samples (nyet soil or plant matter may leave the country) to be taken home for analysis. Later today they’ll inventory and box lab equipment (micro plates, ammonium vials, Van Dorn samplers, soil corers, increment borers, and permafrost probes, biomass quadrants, DBH tape, clinometers, trilogy fluorimeters, and about the only piece of kit I could identify without help, Ziplock bags) that will stay behind for next year. Twenty-two days ago I watched them unpack and assemble this esoteric stuff, and the mood today as they repack it is far more subdued. This is our last full day on the Kolyma River.

Supplies and luggage sit on the floor of the wet lab waiting to be packed for the journey home or stored to await the arrival of next year’s researchers. © Becky Tachihara

Endings, we learn before we’re old enough to read about them, are a fundamental truth of human experience, but that’s no reason to like them. Month-long expedition endings evoke a particular sort of bittersweet poignancy. We’ve come as strangers from all points of the compass to live in very close quarters, on a barge in this case. We’ve grown not merely to accommodate each other’s foibles and eccentricities, but to enjoy them as an aspect of our common purpose and shared experience. We’ve become friends. And then, abruptly, we part. Maybe not permanently; maybe we’ll stay in touch, but the context will be absent. This is meaningful only to those of us who were there, but it’s hard now not to think of the experience in personal terms.

The Polaris Project and its important purpose will abide. The National Science Foundation has announced funding for the next three years. (After breakfast, Max would ask about research plans, by saying, “Okay, what are you going to do today for the American taxpayer?”) For the past, present, and future life of the project, Max deserves much credit, but so too do the PIs, most of whom, barring the unforeseen, another fundamental fact of life, will return to supply continuity. The concept—a combination of education and pure scientific research—works. I’ve watched it work and doing so learned a lot about the energy contained in common purpose and about this sort of Earth science.

Jorien and Juan Carlos pour over data in the main room of Orbita. As everyone wrapped up their lab work, more people gathered in Orbita, laptops open, to analyze data. © Becky Tachihara

But we wish that these happy facts were unalloyed by that darker one at the heart of the project’s scientific purpose—to investigate and document the present state of nature in the Siberian Arctic while it’s changing beneath our feet. Several of us were discussing climate change yesterday in the context of timescales after a talk by a Russian paleontologist. He ended it by saying that he didn’t believe that global warming would last for long.

“What do you mean by ‘long’?” John asked.

“About a thousand years,” the Russian replied.

A thousand years…. Yeah, from the detached perspective of geologic time, we can see Earth change from glacial to inter-glacial periods, evolution to mass extinctions and back again. We see that Earth abides through the changes, and the eye-blink timescale of human lifespans don’t much matter. The Arctic won’t die, even if the polar bears do; it’ll just be a different place, a tick of the geologic second hand for later generations of scientists to explicate. But this is too sanguine, even reductive. It’s like saying, sure, there’s injustice, oppression, and poverty in the world, but then, there always has been. No, the now matters. Never before in history have humans owned such power as we do now. We’re used to our power to replace entire ecosystems with things to serve our interests and next-quarter earnings. As Zimov would have it, we did that in Siberia way back in Pleistocene times when we killed off the big grazers. But our present power transcends that needed to eradicate ecosystems. Our power is changing the world’s climate; it’s geophysical in scope, and to exercise it all we have to do is nothing. That has to mean something for right now and for tomorrow. Never mind the next eon, at least for now.

I don’t know, maybe I’m just feeling a little melancholy over endings. Twenty-four hours from this writing, we’ll be back in the air. Cherskii-Yakutsk- Moscow-Washington D.C.—then dispersal. But I hear people in the next room laughing about something. There’s been a lot of that, laughter, since we left D.C. seemingly so long ago, yet the time has passed in a finger snap.

An intriguing cloud formation hangs over the taiga, dyed shades of pink and orange by the sunset. © Becky Tachihara

Late last night the Arctic put on one of its inimitable sky shows. No doubt it’s cued by a mixture of particle-free air, complex weather systems, high-latitude light refraction, and ice, but, watching the fantastic colors and the dynamics, you don’t think much about scientific explanations. The show is spectacular, evocative, moving, almost unbelievable as if composed by an over-caffeinated Romantic scenic painter. And only a reckless writer with a lot of space and time would try to evoke it in words, except to say that once you’ve seen the show, you never forget it. The memory of that sky is one of the reasons why we love and long to return to the Arctic. But it also brings us to the ending.

We’ve stayed two nights in what we’ve come to call our “hotel-like structure” on the outskirts of Moscow. The students have verbally presented the findings from their individual projects; we’ve seen a bit of the big city, and just finished our last meal in Russia. Tomorrow we fly ten hours to Washington. “When does it end?” Max asked in an after-dinner speech. Did it end when we said goodbye to the Zimovs, the Davidoffs, Valentina, and the others at the barge? When we took off from the Cherskii airstrip past the crashed planes on the edges of the runway? When we left Yakutsk, our last stop in Siberia? Here in Moscow or tomorrow in D.C.? Or maybe, Max suggested, it never ends in memory for those of us who’ve lived it.

Anyway, I don’t want to go all runny. And there’s threat of Karaoke in the air, so I’ll close. I’ve had an unforgettable experience, and I’m not alone in that. Best of luck to the student scientists, the PIs, and to the future of the Polaris Project, and the future of the Arctic (and of Polaris the dog.)

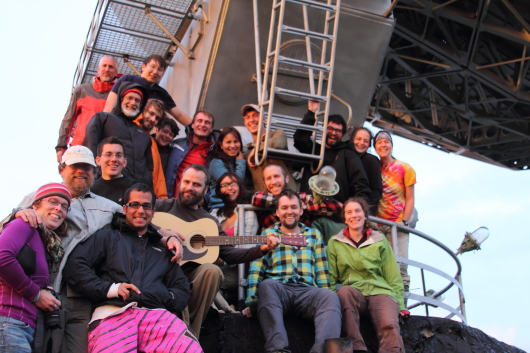

The group gathers on the roof of Orbita to watch a spectacular sunset and enjoy one of our last nights in Cherskiy. © Becky Tachihara

Comments(2)-

Eliz says

August 10, 2011 at 2:02 pmThe image of the cloud is amazing, I never seem to be able to capture this kind of sunset photos without them coming out blurry.